Romanian teenagers and the Internet: The Internet in the life of romanian adolescents

Simona Stefanescu

Romanian Adventist Theological Institute, Cernica, Ilfov, Romania

Since the beginning of the `90s, the Internet has revolutionized the

communication world in unprecedented ways. No other medium managed to

achieve this, and the Internet along with other

technologies has opened channels of communication different from all

the classic ways of communicating. Its potential of altering

traditional communication systems turned into an important subject of

research in the field of communication.

The research this article is based upon is included in the wider trend

of social-constructivist paradigm, which looks upon people as if they

were the ones to build their own realities and social identities, by

the means of interacting with others and projecting their cultural

expectations, respecting the general rules of social life at the same

time. Looking at it from this perspective and trying to explain the

agenda of common internet users, regarded from the point of view of

their relationship with technological systems, A. Feenberg (1991, 1999)

came up with the `critical theory of technology' according to which these

systems are not able to define in an exhaustive way the necessary

conditions for the existence of the subjects involved in it. People use

to offer their own explanations and they generate their own

applications when it comes to technological systems, but most of the

times these aspects turn to be far away from their initial goals.

According to Feenberg, they are not irrational alterings, the way the

dominant ideology might portray them, but rather a pattern of

rationalism, deeply rooted in the alternative values and interests set.

Based on this idea, the users, the clients and even the `victims' of

technological systems engage in appropriating technology in a creative

way, causing its reform and hence making it appear more humanized, even

democratical.

Starting from this wider perspective, M. Bakardjieva and R.

Smith (2001) introduced the term of `generative process of technology',

in order to characterize the dialectic nature of technology, regarded

as a system that not only determines, but is also able to transform,

inside the wider ring of technology at the disposal of people. This

vision allows us to see the Internet -at the same time- as a system

that determines what the users can do and cannot do, endorsing an

`already given' design, and as a system able to alter during its usage.

The same authors refer to the `little behaviour genres' emerging as a

result of several typical usage situations - ranging from the

loisir when at home to the usage in an

organized system, at work - but each one of these situations

represents a result of the social environment, determined by the larger

process of social reproduction (Bakardjieva & Smith, 2001, p. 68).

Starting from these premises, the idea that the Internet users are

indeed an active force in the `generative process of technology' might

emerge, as a hypothesis, but not in any random or voluntaristic way.

The socio-biographical situations in which the subjects find

themselves determine specific `little behaviour genres', where the ways

of using technology are also included. If certain conditions are met,

such genres are able to induce changes in the technology itself.

However, their existence is a factor that brings its contribution

towards creating possibilities for the development of the

aforementioned technology.

One might argue that the researchers from the communication

field found themselves somehow unprepared in front of the impact of the

Internet development. Besides the initial difficulties triggered by

conceptualization (for instance, there were questions dealing with the

classification of the Internet as medium: a mass communication agent,

or a way of interpersonal communication?), then there were the

difficulties in using it, explaining all the aspects, the theories and

the theoretical models existing at that time. Despite the fact that

some theories related to communications can be used when

studying the Internet's effects and implications, we are in

need of new concepts and theoretical models, through which the

evolution, the usages and the effects of this new medium could be

interpreted. Although some progresses have been made lately, due to

several approaches from the communicational, sociological,

psychological perspective and so forth, at present the development of

technology (of the medium itself), is still ahead of the researches

regarding its social impact.

Objectives and Methods

This article presents some of the results of a

research

1 whose objectives attempted to identify: a) the extent to which

Romanian adolescents have access to the Internet and the

characteristics of this access; b) the patterns of using the Internet

and the conveyance of a `portrait' of the Internet uses, of the place

of the Internet consumption into the larger media consumption, on one

hand, and in the customs of interpersonal communication, on the other

hand; c) the effects the Internet has on young people, both on the

personal plan, and on the plan of social micro-relationships, not to

mention the wider plan of social life; d) the expectations towards the

Internet - not only personal, relational and social ones, but also

the expectations related to technological evolution.

The specific objectives of this paper are identifying: the frequency and

the duration of adolescents use of the Internet, as well as determining

the most frequent used applications; access to the Internet and the

characteristics of it; the significance of the Internet for the

Romanian adolescents (what does the Internet mean for them?).

The methods we used were specific both to the qualitative and

quantitative research: in-depth interviews and sociological survey.

Using the qualitative method, 30 respondents have been interviewed

in-depth, chosen according to two main conditions: a) still studying

in high-school; b) using the Internet. As both the qualitative and

the quantitative researches aimed samples of respondents from

Bucharest

2, a third criterion was added: the respondents should live and

study in Bucharest. Specific criteria for choosing the respondents

consisted of independent variables, such as gender, year of study,

profile of the high

school

3 . The interviews were conducted between March-June 2007.

The sociological survey was fulfilled on a representative sample

of teenagers from Bucharest, and the sampling technique was the

`strata' one. The sampling schema was complex, involving a bistadial

sampling procedure, combined with proportional strata operations,

cluster selection and random simple selection (standing for the last

selection type). `The universe of the research' or the reference

population was made up of adolescents living in Bucharest, studying in

high school. `The strata' the sampling was based upon were: a) the form

of education (highschool, with three variants: `day'

education, `evening' education and reduced frequency,

respectively vocational/professional schools); b) the year of study

(with five subcategories - 9,

10,

11,

12 and

13) and c) the `profile' (with

eight types/substrata - human sciences, real sciences, informatics,

economic, artistic, sports and technology). The highschools where from

the respondents have been selected, the classes (parallel classes, such

as - A, B, C, D and so on), as well as the pupils who took part in

the survey were selected by random allocation. The field survey was

carried out in November 2007, in 60 highschools and vocational schools

from

Bucharest

4, and the volume of the final samples reached 1008 subjects.

Results

The frequency and the duration of adolescents use of the Internet

The results of both the qualitative and the quantitative

research show the fact that adolescents can be considered `intense

Internet consumers'. 29 out of 30 in-depth interviewees use the

Internet

daily, and our sociologic survey

showed us that more than three quarters of the teenagers use the

Internet daily.

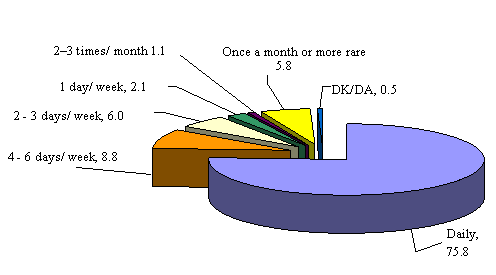

Figure 1: The frequency of Internet use by adolescents (percents)5

Figure 1: The frequency of Internet use by adolescents (percents)5

Therefore, 75,8% of the subjects use the Internet daily, and almost

17% do not use it on a daily basis, but at least once a week they use

the new medium (8,8% of them get online 4-6 times/week).

The data provided by the in-depth interviews allowed us to

find out what is `hiding' behind these figures. Besides noticing that

they use the Internet daily, we were interested to find out what this

`every day' means. The qualitative research revealed the fact that the

duration of using the internet varies from one hour to 10 or even 13

hours daily. Some of the in-depth interviewees were not able to

estimate how much time they spend online: they state that their PC or

laptop connected to the Internet is switched on `all day long', without

using it continuously, because there are other activities going on

during this time, or they stop using it in order to perform other

activities

6:

Cassette 1

"It's switched on all the time"

| Sanziana

(11 grade, 18

years old): "[When do you use the

Internet?] Every day (...) Ever since I come back from

school, until I hit the sack. But I do not stay at my desk all the

time, sometimes I go out and I leave it switched on, because the

Messenger runs all the time. I chat all the time; this is some sort of

addiction. If I do not get online for one day or two days, I feel I am

going crazy!"

Oana

(11 grade, 18

years old): "Using it passively or actively?... Because,

practically, the access to the Internet begins with every on-switch

of the PC and it is on all the time. Hence, I am online all the time.

When it comes to browsing the Internet pages, or communicating via

Internet, this means about two-three hours per day, on

average".

Lavinia

(10 grade, 17

years old): "I own a PC, it's in my room, and the Messenger

is on all the time..."

Doina

(9 grade, 16

years old): "I switch it on in the morning, I leave it like

that and when they call... I mean, I do not stay in front of the PC

all day long, only when I have something to do or other things like

that. I do not use it only for chatting". |

|

As one might easily see after reading the latest two statements, the

Internet is equated, many times, with the Messenger or with the

activity of `chatting, communicating'. Anyway, communicating with other

people, especially instant communication is the main factor driving

towards adolescents using the Internet.

Going back at the amount of time spent online every day, we find the

examples offered by teenagers quite relevant - taking into account

the fact that they spend all their free time, or almost all of it,

online. Even on workdays, when they have classes, some teens spend even

10-13 hours/days, as one can notice in the examples provided by the

second cassette, or at least four hours per day, as cassette number

three shows:

Cassette 2

"10-13 hours daily"

| Cosmin

(10 grade, 17

years old): "13 hours every day, usually; it depends on how

much free time I have when I am at home, but on average I would say

about 10 hours".

Adrian

(11 grade, 18

years old): "It depends on the time. There are times when I

use it 10-12 hours daily... It depends on my training

program7 ". |

Cassette 3

4-5 hour per day, sometimes even more"

| Maria

(12 grade, 19

years old): "On average, about five hours every day

(...) During weekends, even more, and weekly about 40 hours".

Mihai

(12 grade, 18

years old): "About five-six hours per day".

Alexandra

(11 grade, 17

years old): "About five hours every day, maybe six or four,

it depends on the day (...) During holidays there are days when I

get to stay online from dawn till evening, mmm, I mean, using the

PC".

Stefan

(9 grade, 16

years old): "On the average - four-five hours/day,

sometimes even more than this. And every week this means a lot, around

35 hours, according to my assessment".

Sorina

(9 grade, 15

years old): "I guess it is around five hours/day. (...)

In weekend I get to spend more time online". |

|

Starting from these examples, one might notice the subjects

differentiate between using the Internet during workdays, weekends and

holidays. This is precisely why the questionnaire we used during our

survey had a decomposed item of three periods of time, emphasizing the

differences between the adolescents' agenda: workdays (Monday to

Friday), weekends and holidays. We underlined this difference due to

the fact that our previous qualitative research, as well as

most of the studies referring to mass media consume - show

that the period of time assigned to the media is not a homogenous one,

being correlated to people's daily agenda.

Figure 2: Duration of the Internet usage according to adolescents' agenda

(users' percents)

Figure 2: Duration of the Internet usage according to adolescents' agenda

(users' percents)

As one might easily notice in this graphic expressing the results of our

survey, more than half of the respondents are Internet power users

(spending more than three hours per day on the Internet), even on

workdays, when they have to go to school the next day. Thus, the

cumulative percents expressing the subjects who use the new medium for

six hours/day, four-six hours/day and three-four hours/day reaches

52% during workdays. The percent gets even higher when it comes to

using the Internet on weekends and holidays: 66,8% of the respondents

use the Internet for more than three hours every day during the

weekend, and the percent gets grow to 71,9% during holidays. This

growth shows us that adolescents feel constrained by the school

program. One should also take into account the `intensive internet

consumption' during holidays: almost half of the teenagers (45%) spend

more than six hours per day online when they are during holidays.

Furthermore, this percent also is significant during weekends (33%),

and on workdays, when 17,9% of the teenagers use the Internet for more

than six hours per day, although they have to go to school the next

day.

Internet access

All the in-depth

interviewees subsequently answered that they

get online from home: "home" is the main location from where the

Internet is being used, even the only place,

most of the times. In some cases, the

subjects presented other locations too, such as

school, Internet Cafes, friends. The school

is mentioned only a couple of times as location for the Internet usage,

and when they get online from that location they do not do it in

educational purposes (they do not use it in order to learn something

new or help the educative process developing during school program). On

the contrary, using the Internet from school appears to be an illicit

action, taking place during the breaks or after the informatics classes

are over, so the educative process had already reached its end.

Usually, they use it to check the mail boxes and the messages sent to

them from different web sites:

Cassette 4

"At school, only during break time"

| Oana

(11 grade, 18

years old): "At school, only during break time, provided

that the teachers allow us. [From the

classroom?] No, at the lab,

during the 10 minutes long break, they allow us to get online and do

whatever we want. [And would you rather use those ten

minutes to get online?] No.

Honestly speaking, 10 minutes it's not enough times for what we are

interested to do online. Anyways, there's not much to do in 10

minutes". |

|

On the other hand, when they are at `home',

all the interviewees use the

Internet, some of them do it

only from home. The respondents use the Internet all by themselves; using it

with someone else is an exception, not something happening frequently.

The exceptions happen when friends are visiting, when getting online

together is a habit for checking the Messenger or the messages on the

sites they have subscribed to. `The norm' is accessing the Internet

when alone, and most of the respondents (24 out of 30, in the case of

in-depth interviews) from ones room. Sometimes the teens' room turns

into an exclusively private place, as Oana states:

Cassette 5

"I prefer to get online when I am alone, from my own private space"

| Oana

(11 grade, 18

years old): "I get online using the PC in my room, this is

my private personal space and no one interferes with it (...) I

have my own room, my TV set, my PC, my phone, my bed, my books -

everything in there belongs to me. And I usually connect to the

Internet from my room, it's my own private

space, where I am alone. So there is no one beside me, unless, let us

say, I might invite someone to visit and we see some websites". |

|

The survey confirmed the results we got during our in

depth-interviews, as 87% of the respondents confirmed that they get

online from their homes:

Figure 3: Locations to Internet access by the adolescents

Figure 3: Locations to Internet access by the adolescents

The high percentage (87%), shows us the fact

that there is a high degree of connectivity to the Internet (at least

in the families of teenagers), despite the fact that about four years

ago, in 2004, a national

survey

8 showed that the percent of the degree of

connectivity to the Internet was of only 6% (11% in urban areas and

1% in rural ones), in the households where there was at least one

child aged between 6-18 years.

The major differences between the data achieved by the two surveys can

be explained by appealing to two elements: the difference between the

reference population (our survey was focused on respondents living in

Bucharest, while the one that took place in 2004 was at national

Romanian level, and the statistic data show us that Bucharest is

leading the ranking referring to Internet connections), and the second

element refers to the three year interval between the two researches,

which turned out to be a good time for altering the peoples'

conceptions in what the Internet connectivity is concerned.

Furthermore, as we envision adolescents, we have to take into account

the greater pression they put on their parents, so that they can get an

Internet connection at their place (usually cable). But pressure aside

(one could resist to it), the parents willingness to provide their

children with an Internet connection can be explained by the image of

`encyclopaedia of all encyclopaedias' that the Internet has achieved.

As our research has revealed the ambivalent character of the Internet

(medium of information and communication, at the same time) - is

responsible for this opening towards the Internet: the parents

appreciate its informative features, while the teens value its

communicational characteristics).

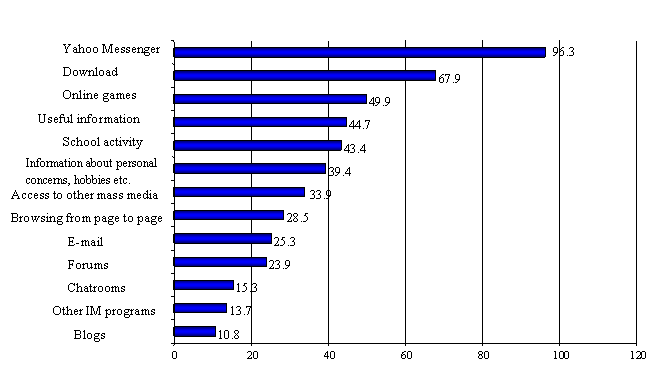

The most used applications/programs of the Internet

The item referring to the most used

applications/programs of the Internet

was assessed using a hierarchic

scale

9, and these are the results:

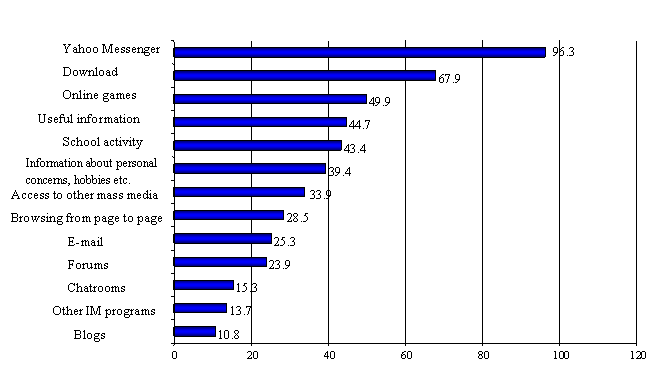

Figure 4: The most frequent used applications of the Internet by adolescents

Figure 4: The most frequent used applications of the Internet by adolescents

This graphic strengthens an already established hierarchy,

conveyed by the in-depth interviews: for

adolescents, the Internet means

communication, entertainment and access to information. In order to

communicate, the leading program, ahead of other IM programs, is Yahoo

Messenger. 96,3% of the respondents designated it the main program

that justifies the usage on the Internet. Yahoo Messenger means

communication, this is its very essence, and it does not deal only with

instant communication, in real time (and here we include written

communication, voice to voice calls from one PC to another, and visual

communication via webcam). They also communicate the features of their

personality, preoccupations and frames of mind, through the means of

avatars and displayed messages, their constancy versus frequent change

and so on.

The next two applications popular among teens are the "download" and

the "network games" - both of them can be included in the field of

`entertainment', as the Internet users have labelled it, while the next

three items of the hierarchy give meaning to the `information' field:

useful information, pieces of information for the school activities,

various other types of information (related to interests, personal

preoccupations, hobbies and so forth). The other applications mentioned

in the graphic subscribe both to communication (such as the e-mail,

chats, IMs, forums, blogs) and to information (access to other mass

media types, browsing from one page to another) - but the latest

ones might as well be associated to entertainment.

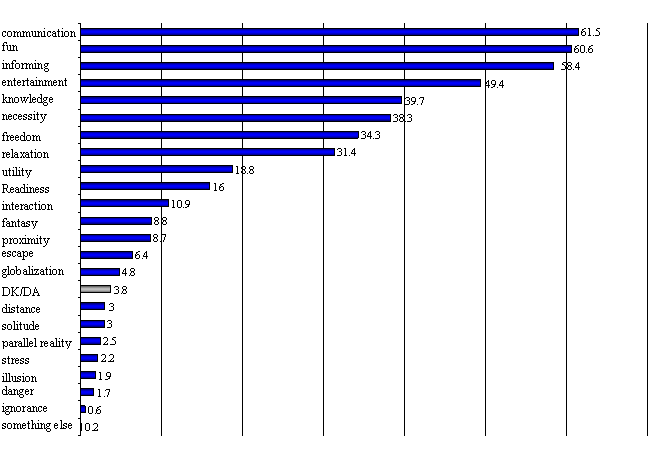

The significance of the Internet for the adolescents

In order to find out what the Internet means for the Bucharest

teenagers we asked them, during the sociological survey, to

characterize this new medium of communication using maximum five words.

The results are being shown in the next

graphic

10:

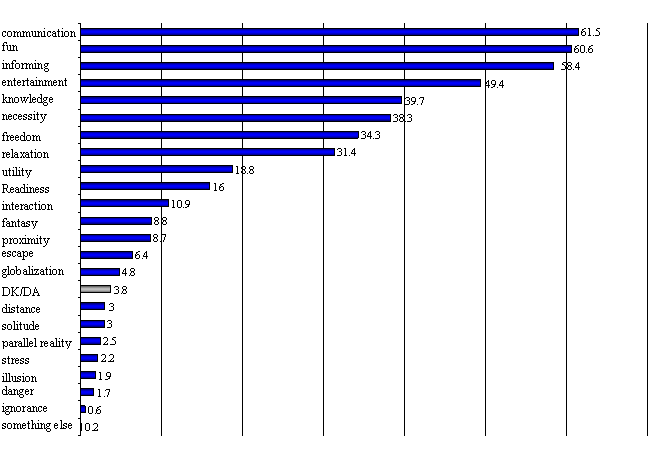

Figure 5: Terms that characterizes the best the Internet

Figure 5: Terms that characterizes the best the Internet

As one might easily notice,

communication is the first word mentioned by 61,5% of the subjects.

Anyway, as our research has shown so far,

adolescents think that the

Internet facilitates the communication between people and it changes

it, at the same time, and the interviewees consider that it becomes

`improved' this way. The previously shown hierarchy (see figure 4) is

confirmed for another time, because the next places are also being

secured by entertainment activities (the

`

fun' title is mentioned by 60,6% of the

subjects, and 49,4% of the respondents indicated the word

`

entertainment', that secured the forth

place in the hierarchy) and

informing (term

chosen by 58,4% of the interviewees).

The next four words from the hierarchy, chosen by close percents

of the respondents do not represent features or `objective', concrete

definitions of the Internet, but symbolical definitions. For

39,7% of the respondents, the Internet mean the

knowledge. This word can be associated both

to `informing' (finding out new things and memorizing them) but also to

`communicating' (getting to meet new people). 38,3% of the respondents

associated the word

necessity with the

Internet, so they regard the Internet as being an integrated and

indispensable part of life. Another symbolical significance associated

to the Internet, revealed also before by the qualitative research, is

the

freedom - 34,3% of the respondents

considered that it defines the Internet in the best way. Finally, the

fourth word of this set -

relaxation -

was mentioned by 31,4% of the subjects, and this significance can be

associated both to communication and to entertainment.

Other features chosen by teenagers in order to characterize the

Internet:

utility, readiness, interaction, can be regarded as positive aspects of the new medium. The same applies

to the characteristics mentioned further, in a set of four words, or at

least the first three terms, because globalization is an ambivalent

concept, being regarded, at least by some of the analysts, as a

negative phenomenon that characterizes the nowadays world:

fantasy, proximity, escape, and globalization.

Finally, what appears to be significant in our research is the

fact that the terms that stand as negative characteristics/aspects that

can be associated (and many specialists, but especially

non-specialists in socio-human sciences associate them in virulent

critics) of the Internet, are in fact a dwindling minority when it

comes to the words adolescents

associate to the Internet. Many people criticizing the Internet assert

that it generates and/or facilitates the distance between people. Only

3% of our subjects chose the

distance as a

word that might characterize the Internet. The critics also mention

that the Internet encourages and determines the lack of interaction

among people, the

solitude, but only 3% of

our respondents see things this way. Many people talk about the reality

created by the virtual world itself, by the Internet, as a `parallel

reality' that damages people's lives. Only 2,5% of the respondents

chose the sintagm

parallel reality in

order to define the internet. So do the ones that criticize this

technology, they see it as if it were another world, another reality,

an

illusion able to waste people's lives.

Only 1,9% of the respondents chose this term. Small percents (under

2,2%) referred to other terms, such as

stress,

danger, and

ignorance - this shows us

that adolescents think that the

Internet is mostly a positive medium, being associated with positive

words, such as communication, entertainment, informing (it facilitates

and improves them), and also with utility, relaxation, fantasy,

freedom, necessity, knowledge and interaction.

Discussions

Our research reveals the fact that

adolescents are Internet power

users. For many of them, staying online turned into the only way of

spending their free time. There are high percents of teenagers using

the Internet daily, and their consuming grows during weekends and

holidays - and this shows that they are being conditioned by their

agenda/school program.

In many cases, `the Internet is on all day long', even on

weekdays (though the pupils have to go to school the next day), and

despite the fact that they do not use it continuously. For some

subjects of our research, the Internet seems to offer a kind of

psychological safety: they are being `connected' all the time and want

to stay connected, even when they are not in front of the PC; this

shows their desire of staying connected to the virtual world. When they

break from it and then come back, after the interrupted

connection, they want to stay in touch with everything that

happened during their absence.

One might ask oneself, at this point: what makes the Internet so

important in teenagers' lives? What does the Internet offer

them, what makes them wish to stay online all the time and spend so

many hours online on a daily basis? We can find some answers when

interpreting the results of our research regarding what does the

Internet mean to teenagers, what is the significance they offer to this

new medium.

There might be the argue that the Internet offers youngsters

many things they want. First of all, it gives them the possibility of

communicating - free of charge - with their friends or with other

teenagers. It is already an axiom, the fact that communication is

fundamental for people. In particular, for the group of population that

makes up our target -

adolescents - communication is

a way of living. The Internet offers

adolescents this possibility of

communicating, not only verbal communication (with multiple

possibilities included - written and oral communication), but also

non-verbal (the

web-cams make the

communication through mimics and facial expressions possible).

Communicating via Messenger gives the teenagers the possibility of

offering others information about their personality, their interests

(general or on the spot ones), their tastes and so forth. Communicating

via websites such as Hi5, for instance, is complex: some sort of

miniature radiography of the personality of the owner of the page. Such

a page offers others details on its owner: whether it is an introvert

or an extrovert, whether he/she has many friends or not, if it is a

popular person or not, not to mention the details connected to the

favourite books, music, the teenagers' category where one belongs (for

instance, rockers are a category that does not mix up with housers or

hip-hoppers and so forth).

Communicating over Internet means not only keeping in touch with

the friends and the people one knows in `real life', but also

communicating with `virtual friends'. Most of the

adolescents prefer relationships

and friendships that exist in real life that is way most of the time

`the virtual friends' turn into real friends. However, many teenagers

bestowed the power of `knowing' upon the Internet - and they were

also referring to meeting new people: Internet facilitates it. We were

talking about the possibilities of telling others about ones tastes,

interests, personal preoccupations - they are extremely diverse,

multiple, and teens have the chance to meet other teenagers like them.

Taking into consideration this point of view, communication over

Internet means more than communicating via phone (and replacing it,

because the Internet provides free calls, they only have to pay for the

monthly subscription): the telephone does not offer the possibility of

meeting other people, at least not on a wider scale, and on the

Internet one is not limited to the verbal communication.

Many times, the Internet is being regarded as the equivalent of

communicating - for instance, when being asked about the Internet,

the teenagers' answers involved (Yahoo) Messenger. This application is

used active (sometimes is equated with the proper use of the Internet)

and intensive (as many adolescents told us, they sometimes have over

six online conversations simultaneously). This fact entitled us to say

that the Internet, indeed, concur to communication facilitating (in

adolescents' terms), but also to changing it. Communication over the

Internet is a `transformed' communication.

Besides communicating via Internet,

adolescents use it in order to

inform themselves and for entertainment. Practically, the possibilities

for entertainment offered by the Internet have no limit, and most of

them are not available in any other mass media genre. For instance, the

network games offer teens the possibility of competing against

each other, testing their abilities and intelligence (when it

comes to strategy games) or their knowledge, memory, logical thinking

or intuition (general knowledge games). On the other hand, the Internet

is a gate of access towards music and movies, two of the major

preoccupations of adolescents. The

TV and radio stations also broadcast such shows, but on the Internet

one might find whatever one wants, and it can be downloaded, not only

seen. The TV and the radio impose a limit - the one of seeing some

things that has already been rotated and set in a program - but the

Internet offers the `freedom'. People can choose the movie they want to

see or the music they want to hear, and teens appreciate this freedom.

Information is also easier to assimilate from the Internet. By the

means of the Internet, adolescents

get to know information that might be useful for school, for their

future job, for their general knowledge, information regarding their

own interests, news and so on. Besides, they have the freedom of

choosing the pieces of information they are interested in, without

feeling constrained by a program or a certain horary, such as news

broadcasts shown on TV.

The Internet has turned into an integrated part in

adolescents' life, in their

quotidian `rituals' and as one of our interviewees has said `we cannot

imagine life without the Internet'. We should emphasize the fact that

many teenagers do not see any harm or anything wrong in what the

Internet is concerned. One possible explication states that they grew

at the same time with the Internet: for them it is not a new medium, it

is just part of their daily life and routine and they associate it only

with positive words. Many adults went into overdrive when classifying

the Internet as a dangerous medium, because there are no restrictions

and no censorship, a space where freedom is not well understood, a

factor leading to stress and to waste time, a way of distancing the

people, a space in which human interactions are lost, in which the

ignorance is promoted and the desire of human beings to learn is

destroyed. Our research proves the fact that most of the teenagers do

not associate any of these negative aspects with the Internet. On the

contrary, they associate it with the utility and relaxation, with

fantasy and with freedom - as a fundamental human value, exclusively

positive. For adolescents, the Internet is a space favouring knowledge,

as opposed to ignorance, a space where one can relax, instead of

getting stressed, and the reality provided by the Internet has turned

into more than an intrinsic part of their life, so no one can classify

it as being `parallel' or illusionary.

The Internet has turned into a routine for teenagers, it became an

`ordinary' routine, as opposed to `the extraordinary'. Many teenagers

became a kind of `specialists' when it comes to routinely usage of the

Internet, and this means many times focusing on the communication with

friends, first of all. As I already stated before, communication via

the Internet is a sort of `transformed communication'. Thus, this

particular `specialization' itself turned into the paradox of using the

Internet and dealing with its effects: the more young people focus on

`communicating' and get to spend more time chatting with friends

(generally using IM programs), the lonelier they become - and they

would rather use the internet all by themselves, from the privacy of

their own room. In this case, one might ask this question: where does

the truth stand? Does the Internet facilitate communication and social

relationships (as many teenagers reckon) or, on the contrary, it acts

like a barrier in their way, by encouraging solitary life, in front of

the PC or - depending on how one views things - behind the screen

of a monitor? This problem, like many others, might represent a

challenging research subject for all socio-human sciences.

Bibliography

BAKARDJIEVA, M. & SMITH, R. The Internet in

Everyday Life, New Media &

Society, Sage Publications, vol. 3 (1),

67-83, 2001.

-

- BARAN, S.J. & DAVIS, D.K. Mass Communication Theory.

Foundations, Ferment, and Future.

Belmont: Wadsworth, 2000.

-

- BAYM, N.K, ZHANG, Y.B. & LIN M.C. Social Interactions across

Media. Interpersonal Communication on the Internet, Telephone and

Face-to-Face, New Media & Society, Sage

Publications, vol. 6 (3), 299-318, 2004.

-

- CAPLAN, S.E. Preferences for Online Social Interaction. A Theory

of Problematic Internet Use and Psychosocial

Well-Being, Communication Research, vol.

30, no. 6, December, 625-648, 2003.

-

- DEVITO, J. Human Communication. New

York, Cambridge, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Washington, London,

Mexico City: Harper & Row, 1988.

-

- FEENBERG, A. The Critical Theory of

Technology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

-

- FEENBERG, A. Questioning Technology.

London: Routledge, 1999.

-

- KIM, S.T. & WEAVER, D.

Communication Research about Internet: a Thematic Meta-analysis", New Media & Society, Sage Publications,

vol. 4(4), 518-539, 2002.

-

- MORRIS, M. & OGAN, C. The

Internet as Mass Medium, Journal of

Communication, 46 (1), 39-50, 1996.

-

- SHADE, L.R., PORTER, N. & SANCHEZ W. You can

see anything on the Internet, you can do anything on the

Internet!: Young Canadians Talk about the Internet, Canadian Journal of Communication, Vol. 30,

503-526, 2005.

-

- THOMPSON, J.B. The Media and Modernity: A

Social Theory of the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995.

-

- VALKENBURG, P.M., SCHOUTEN, A.P. & PETER, J. Adolescents'

Identity Experiments on the Internet, New Media &

Society, Sage Publications, vol. 7 (3), 383-402, 2005.

-

- WIMMER, R.D. & DOMINICK, J.R. Mass Media

Research: An Introduction. 6th Edition, Belmont: Wadsworth,

2000.

Footnotes:

1The

reasearch is named

The social and cultural impact of the

Internet on Romanian teenagers, financed by The National Grant of

Research CEEX-ET no. 172/2006-2008.

2Because

of financial reasons.

3This way,

depending on these variabiles and taking into account the general level

structure of the category of population, our in-depth interviews'

sample consisted in: according to gender, 16 girls and 14 boys;

according to year of study, 7 pupils in the 9th grade, 8 in the 10th

grade; 7 pupils in the 11th grade; 8 pupils in the 12th grade;

according to the profile of the highschool, 7 pupils studying at a

highschool with mathematical profile, 8 in humanistic profile

highschool, 4 pupils studying at a technical highschool, 4 studying at

an art highschool, and 3 in sports highschool.

4Out of

102 highschools and vocational/professional schools in Bucharest.

5DK/DA

means `I do not know/I do not answer'

6The

cassettes contain quotes from the answers provided by the in-depth

interviewees; the graphics show the results of the sociological survey.

7Adrian

studies at a sport highschool.

8Reasearch

conducted by MMT (Metro Media Transilvania) and

Gallup for CNA (Consiliul Na tional al Audiovizualului).

http://www.cna.ro/cercetari/sondaje/rapfinrom.pdf, last accession 15

March 2009.

9We asked

them to provide an answer out of 13 variants, 5 answers according to

their opinions; we got 4891 answers; the figure presents percents per

interviewees - on each line.

10The item

was measured by asking the question: What's the word

that characterizes the Internet in the best way, in your view?'. The

respondents have been provided with a list of 23 words, and they were

asked to choose maximum five answers out of them, according to their

opinion. So it was a close-ended question, with multiple answers,

with a nominale scale. As a result of the research we obtained 4624

answers, and the percents from the graphic are being calculated per

respondents - on each line.