Nico Carpentier1, Niky Patyn2

MUDs and Power

Reducing the democratic imaginary?

ICTs and the democratic imaginary

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have received ample attention as potential tools for democratic innovation. Without entering all too deep in the discussion on this utopian claim, it should (at least for now) be noted that the emerging virtual communities were seen as one of the promising areas for new (democratic) practices to take place. Although critical voices were soon to be heard, they usually focused on retorting the utopianism. This article wants to take these analyses one step further, by not (just) arguing for ordinariness in stead of newness (including the "normal" presence of disciplining and surveillance (Lyon, 1994)), but by analysing the extraordinary quasi-authoritarian power relations in two specific virtual communities, both Multi User Domains/Dungeons (MUDs).

We knowingly enter with this choice into the world of play and fantasy, but at the same time we want to avoid underestimating the importance of this sphere. All forms of human encounter need in our opinion to be considered vital learning sites through interaction (as was already argued in symbolic interactionism). This social learning also immediately includes democratic and political learning, if a broad definition of democracy and politics is accepted. From this perspective MUDs act as virtual places where subjects are confronted with the workings (or micro-physics as Foucault would call them) of power, authority and hierarchy. Although the specificity of these playful environments also needs to be respected, MUDs cannot remain imprisoned in the un-real. The discourses that are produced at the level beyond the un-real through the mediation of play become again (politically) very real and relevant.

In order to show this reality, we have analysed the power relations in two MUDs, using a methodology based on participant observation. This analysis is theoretically framed by the key concepts of play and power, a discussion, which we will commence first.

MUDS as playful on-line communities

Pavel Curtis (1997: 121-122), creator of LambdaMOO

3 and researcher at Xerox PARC, proposes the following definition for MUDs, which is unfortunately again characterised by an emphasis on the used technology. Despite these shortcomings, it still proves to be a decent starting point.

A MUD is a software program that accepts "connections" from multiple users across some kind of network (e.g., telephone lines or the Internet) and provides to each user access to a shared database of "rooms" , "exits", and other objects. Each user browses and manipulates this database from "inside" one of those rooms, seeing only those objects that are in the same room and moving from room to room mostly via the exits that connect them. A MUD, therefore, is a kind of virtual reality, an electronically-represented "place" that users can visit.

Types of MUDs

Another approach towards defining MUDS is to categorise them, and to take into account the diversity of MUDs. According to Hart (2003), an author writing for the Agora-website, which evolved out of the MUD-dev (short for MUD-development) mailing list at Kanga.nu, these MUDs can be categorised in three major categories: chatters/talkers, levelling games and pure role-playing games. Of course, this classification is in reality seldom as straightforward as this. The majority of MUDs is a mix of two or even all of these categories, combining for example the levelling aspect with role-playing.

A. Chatters/talkers

Chatters are also known as social MUDs and run on code bases such as TinyMUD or MOO

4. A social MUD is a "safe" place, in such that it contrasts with "dangerous" adventure MUDs, where people can come together to talk. They don't have to worry that other players or monsters will kill their characters, nor do they have to make sure their character eats and drinks enough to stay alive. The focus is on social interaction and not on survival, as is the case with levelling games. The hierarchy on social MUDs is not as strict as on other MUDs and the player ranks are based on interaction and contribution (Reid, 1999: 125-126)

5.

- [OOC] Mudder117: "are there penalties for being hungry/thirsty?"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "you don't heal as fast"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "but that's it. You can be hungry indefinitely and never starve"

|

B. Levelling games

Levelling games or adventure MUDs (mostly running on Diku- or LP-servers

6) differ strongly from the social MUDs in several ways. The MUD environment is "dangerous" and the characters can die, and do so quite often too. The characters are subject to "natural" forces such as hunger, thirst and exhaustion. And besides that, they are regularly confronted with monsters that can shorten the characters" lifespan considerably. The focus of the game is to survive and this constant danger translates into strong ties of camaraderie between the users of the MUD. The hierarchy is often strict and based on competition and strength.

- [OOC] With horror, you realise your body is decaying into dust. You try to shout out, but all that remains...is darkness.

- [Info] Dimmu has died due to malnutrition!

|

C. Role-playing

Role-playing MUDs can be both social or adventure oriented. The only difference lies in the way in which the users communicate with each other, since it is determined by the setting of the MUD. In a Star Trek environment, the player is supposed to adopt Star Trek-jargon, while such a mode of communication will not be welcomed in Tolkien-based MUDs. Blackmon (1994: 629) poses that the users are encouraged to become their characters and to act out their fantasy, albeit within the rules provided by the game design. The success of this type of game lies, according to Toffler (1970) in his analysis of the "old" Dungeons & Dragons, in the fact that it allows the player to "escape" from the routines of everyday life. This, however, is true for almost any type of recreational activity (Lancaster, 1994: 76).

MUDS as play

The above categorisation already shows the main weakness of Curtis' definition, as the user and the specificity of user practices in a MUD-environment are disregarded. Firstly, Remy Evard (1993: 3) underlines in his definition the importance of the real-time interactivity between multiple users. Curtis' definition incorporates the fact that the server accepts connections from multiple users, but it leaves out the interactions that construct this online environment. An even more important feature refers to the specificity of this interaction, as it is based on the creation of a fantasy world where players take on one or more roles. As Turkle (1995: 182) remarks, a defining element is the distinction

7 between the player and the character(s) of the player.

This allows us to exemplify the importance of the notion of play, especially in the levelling games and the role-playing MUDs. Following Caillois' (2001) classification of games, levelling games are related to the Agon-group, which are games built on competition. Role-playing games on the other hand fall within the Mimicry-group, as simulation is their main characteristic. As Caillois (2001: 19) puts it:

"all play presupposes the temporary acceptance, if not an illusion (...) then at least of a closed, conventional, and in certain aspects, imaginary universe". Despite Callois' scepticism towards the viability of combining Agon and Mimicry - a combination which is

"merely viable" (Callois, 2001: 72) or even

"immediately destructive" (Callois, 2001: 78) - the MUDs that combine levelling and role-playing show that this combination can effectively be realised and sustained. Both types of MUDs can moreover create Ilinx, the third type

8 Caillois distinguishes. Ilinx, or a sense of vertigo is also referred to in the more recent literature on computer-mediated communication as immersion (Murrey, 1997), or being encapsulated in a flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975).

Reverting to play theory also allows highlighting the specificity of MUDs in relation to other types of on-line communities. MUDs are fantasy worlds that facilitate interaction, simulation and competition, which places them in a specific relationship towards non-play (social and political) realities. Sutton-Smith (1997: 106) summarises this by writing that

"play is about the ontology of being a player and the dreams that that sustains." At the same time play provides participants indirectly with

"solidarity, identity and pleasure" (Sutton-Smith, 1997: 106). Although some authors do stress the educational potential of play, especially in relation to children and adolescents (Groos, 1898, 1901; Coleman, 1961; Piaget, 1962; Bateson, 1976; Vygotsky 1977, 1978), play remains important as a primarily autonomous human activity which serves its own purpose. Nevertheless, play as a human activity needs to be culturally contextualised and cannot be seen in isolation from (among many other things) the power relations that structure and construct society:

"talking about the game independently of the life of the group playing it, is an abstraction" (Sutton-Smith, 1997: 106, see also Gruneau, 1980; Hughes, 1983). From this perspective MUDs can be seen as virtual places where, through the mediation of play, discourses on power, authority, hierarchy, participation and democracy are generated and (re)construc-ted.

MUDs cannot be seen in isolation from the networked technologies that provide the communicative medium and form the construction of (on-line) community. Yet again, play theory is instrumental on both levels. An early example is Stephenson (1967), who in his book

"The play theory of mass communication" emphasises the role of media technology and culture by highlighting that all media constitute play forms: audiences that make use of the mass media are for Stephenson essentially at play. Later analysis of networked communication place even more emphasis on the playfulness that is created by the (relative) interactivity and anonymity of the virtual worlds (Turkle, 1995; Aycock, 1993, 1995; Danet, 2001). Haraway's (1991) "Cyborg Manifesto" for instance contains the "ironic dream" of transgendered bodies that are able to playfully free themselves from the limits of human biology and the social inscriptions of modernism. A more down-to-earth example can be found in Danet's work (1998: 138), where she illustrates the "textual cross-dressing" by listing the 11 genders that are available on LambdaMOO and/or MediaMOO. This list for instance includes the so-called Spivak-gender, which provides users with the following terms to express one's gender: "e, em, eirs, eirself', available for playful use.

Play is also related to the construction of community and communal identities. Although the role of play in sanctioning community is often related to festivals, parades and carnivals (Fernandez, 1986; 1991), also other types of play (as for instance those types that can be found in MUDs) generate community. As Sutton-Smith's (1997: 102) discussion of the so-called

"power-oriented ludic identities" shows, the performance of these communal identities can also be aimed towards an outside threat (e.g. a colonising power or the power holders

9). The presence of these antagonistic or resistant identities immediately and necessarily implies processes of exclusion and inclusion. These power tactics are not only situated at the level of "traditional" communities but also play at the level of all different types of community. Here Sutton-Smith (1997: 103) refers to children's play, where for these children

"the most important thing about play is to be included and not excluded from the group's activities".

Power relations in Giddens and Foucault's work

The mere fact that these environments are communities that are formed on the basis of play, does not exclude the presence of power in these playful relationships, as is the case in any type of community. Communities are invested with an enormous potential for solidarity and kindness (as for instance Tonnies (translation 1963) did) and simultaneously regarded as the locations of processes of disciplining and othering. This duality necessitates an approach to power that incorporates both aspects, which can be found in the work of Foucault and Giddens.

Both authors stress that power relations are mobile and multidirectional. Moreover they both claim that their interpretations of power do not exclude domination or non-egalitarian distributions of power within existing structures. From a different perspective this implies that the level of participation, the degree to which decision-making power is equally distributed and the access to the resources of a certain system are constantly (re-)negotiated.

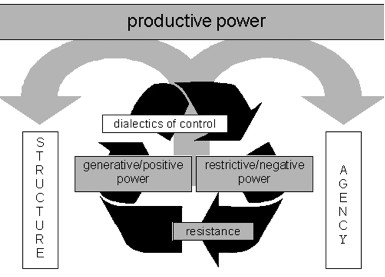

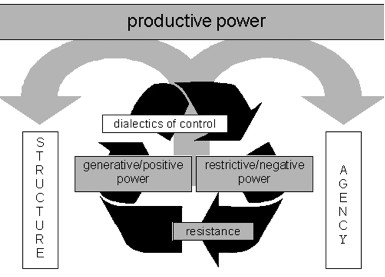

Both authors provide room for human agency: in his dialectics of control Giddens (1979: 91) distinguishes between the transformative capacity of power - treating power in terms of the conduct of agents, exercising their free will - on the one hand, and domination - treating power as a structural quality - on the other. This distinction allows us to isolate two components of power: transformation or generation (often seen as positive) on the one hand, and domination or restriction (often seen as negative) on the other. In his analytics of power, Foucault (1978: 95) also clearly states that power relations are intentional and based upon a diversity of strategies, thus granting subjects their agencies.

At the same time Foucault (1978: 95) emphases that power relations are also

"non-subjective". Power becomes anonymous, as the overall effect escapes the actor's will, calculation and intention:

"people know what they do; they frequently know why they do what they do; but what they don" t know is what what they do does" (Foucault quoted by Dreyfus and Rabinow (1983: 187). Through the dialectics of control, different strategies of different actors produce specific (temporally) stable outcomes, which can be seen as the end result or overall effect of the negation between those strategies and actors. The emphasis on the overall effect that supersedes individual strategies (and agencies) allows Foucault to foreground the productive aspects of power and to claim that power is inherently neither positive nor negative (Hollway, 1984: 237). As generative/positive and restrictive/negative aspects of power both imply the production of knowledge, discourse and subjects, productivity should be considered the third component of power

10.

Based on a Foucauldian perspective one last component is added to the model. Resistance to power is considered by Foucault to be an integral part of the exercise of power. (Kendall and Wickham, 1999: 50) Processes engaged in the management of voices and bodies, confessional and disciplinary technologies will take place, but they can and will be resisted. As Hunt and Wickham (1994: 83) argue:

Power and resistance are together the governance machine of society, but only in the sense that together they contribute to the truism that "things never quite work", not in the conspiratorial sense that resistance serves to make power work perfectly.

Figure 1: Foucault's and Giddens views on power combined

In what follows this model of productive, generative and restrictive power mechanisms and the resistance they provoke, will be applied to the power relations in the world of MUDs.

Power and resistance in two MUDs

In order to show (and analyse) the presence of these power relations in the playful environment of the MUDs, this article reports on the case study of two MUDs (conveniently called MUD-1 and MUD-2). Both MUDs are (each in their own way) a combination of a levelling game and a role-playing MUD. MUD-1 is fantasy-based in the broadest meaning of the word: there are dragons, faeries and ghosts, but there are also Smurfs and light-sabres. The players are free to just play the game or role-play: there is no common theme present. On the other hand, MUD-2 is very rigidly based on the world as described in The Wheel of Time-books by Robert Jordan. This series presently counts eleven books, with Brandon Sanderson finishing the twelfth book after Jordan's death on September 16, 2007. The complexity and rich details of that world are incorporated in MUD-2's areas and the players are thus encouraged to build their role-play around the given setting.

One researcher participated in both MUDs for a period of two months, and these interventions were logged during this period. Eventually twelve logs for each MUD from the first month were selected for analysis

11. The method used for this case study is thus based on participation observation (in gathering the data), in combination with qualitative content analysis, based on Wester's methodology (1995) for analysing the logs that captured the observations. The choice for participatory observation is legitimised by its capacity to study processes, relationships, the organisation of people and events, and patterns, without loosing the connection with the context in which they unfold. Understanding the context is the only way to infer the meaning of complex social situations (Lang and Lang, 1995: 193). Moreover participant observation also has the advantage that it allows the researcher to adjust his/her focus as changes occur in the setting, sometimes yielding unexpected results (Giddens, 1997: 542-543).

Key sensitising concepts for the analysis of power relations in the MUDs, and their (non-)egalitarian nature, can be found in the above discussion on the differences between generative and restrictive power aspects. The focus is more specifically placed on the power relation between the "ordinary" players and the "owners" of the two MUDs. It is contended in this article that the equality in power relations can be analysed by making two comparisons. Firstly the generative and restrictive aspects in the power relations between the different (categories of the) subjects involved are compared. Secondly the restrictions encountered by the players who hold weak powers (Fiske, 1993) are compared with the resistance that these players can exercise vis-à-vis these restrictions. The importance that is attributed to the equality of power relations in the context of play can be found (and legitimised by) the need to hegemonise democratic practices (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985) or to strive towards communicative action - in contrast to strategic action (Habermas, 1984), even in daily life settings that are embedded in fantasy.

Restrictive power aspects

The two MUDs are initially created by a distinct group of people, that own (or rent) the server space on which the MUDs are located. This results in a privileged position for this relatively limited group of people. They, and some of the people they select, acquire spatial control over the area in which the playful mimicry can take place. This spatial control is not limited to the construction phase of (an area of a) MUD, but also implies rights of surveillance and unrestrained movement. Their position is also translated in the occupancy of the top levels of the social hierarchy that is embedded in the competitive form of the MUD, thus bypassing the required need to accumulate points. Moreover, they retain control on who is (in a later stage) allowed to join their ranks. Finally they can exercise regulatory control in order to keep players in line and to deal with recalcitrant MUDders. It is no accident that this privileged group makes explicit reference to a deistic discourse by naming itself "immortals", with the "implementator" at the top of this social pyramid. As the example below illustrates, the immortals' ability to punish and the directness of their regulatory interventions are crucial components in the power relations of the MUD.

- Mudder3 gossips "hey mudder71"

- Mudder3 gossips "didn't mudder2 warn you already?"

- Mudder71 gossips "sorry"

- Mudder71 gossipcs "trigger testing :)"

- Mudder3 gossips "final warning"

|

The two MUDs cannot be seen in isolation from the social. In contrast to what for instance Rheingold (2001) and Castells (1999: 362) seem to suggest, on-line communities still remain communities. As communities they are characterised by the presence of a social structure. The above-mentioned hierarchy is for instance more complex than the basic dichotomy between immortals and "ordinary" players. The accumulation of capital (=points), gained trough the competition (fights with an outside threat or in-fights

12), leads to an increase in status within the player community, translated by upward mobility in the player hierarchy. Players can be granted "immortality" on the basis of their knowledge, expertise and status, although the explicit approval of the implementator (or other high-ranking immortals) remains a requirement. As in most social systems, the regulatory framework is not solely based on the presence of an explicit system of rules, but consists also out of a pattern of norms or informal rules, that are not only imposed by the immortals, but also guarded by all players. Again, one's position on the social ladder of the MUD will affect one's capability to successfully intervene when a social norm is trespassed.

In the following part these components of the dialectics of control are illustrated on the basis of the analysis of the restraining power practices on the two MUDs: four specific elements are distinguished: spatial control, social hierarchy, formal rules of interaction and etiquette / netiquette / MUDiquette.

1. Spatial control

MUDs are vast virtual spheres, consisting of several areas, which all have several rooms. The rooms and areas are created (and known) by the immortals of the MUD. An average area has between 100 and 200 rooms, which can bring the total number of rooms on a MUD from about 3,000 to up to 15,000 and more

13. Areas can be compared with regions or even countries. Mostly, they are designed around a single theme or plot, such as an Elves forest or a haunted mine. The rooms within an area can be almost any type of place that exists in the physical world. So even though they are called "rooms" , they still can be a path in a forest or a stretch of river, as well as a royal audience room or a sewer pipe. These rooms are connected with "exits" that allow players to move from one room to another.

Players have to walk or fly from room to room in order to get from A to B, so it is necessary for them to have enough movement points and to know the way

14. This system obviously forces the players to learn the layout of the MUD by travelling through it, but the immortals can by-pass these restrictions: they can either set their number of movement points to the maximum amount or they can use the "goto"-command

15 that instantly transports them to any place on the MUD.

The creation of rooms and areas also allows the integration of surveillance systems. Some rooms will log anything that happens inside them, while others allow a user to look inside other rooms without being seen him/herself (like a one-way-mirror). Another method is what is called "a trigger". Sometimes, a room will "listen" for a specific event and start a series of actions when it is "triggered"

16. It is obvious that this technique can easily be used to automate surveillance and even punishing. There are also rooms that restrict players from performing certain actions, like killing a mobile - in this particular case a high priest - in what is called a "peaceful room" .

- Chamber of the High Priest

- You have entered the chamber of the most holy man in this city. The High Priest advises the Sultan on all matters in the world of the sacred. From what you have heard however, this holy man has a bit of a temper, and he doesn't look very happy that you've disturbed his prayers.

- The only obvious exit is south.

- [Exits: south]

- (White Aura) The high priest rests here meditating, well he WAS meditating.

- <196hp 172m 210mv> kill priest 17

- It's too peaceful to kill in here18

Other techniques are "snoop"

19, which allows the immortal to see everything the target sees, and the "at" command

20, which lets the immortal manipulate things at another place without having to move him/herself to that place.

Immortals can also create access restrictions: some rooms have special purposes and some are only accessible by certain types of players. How these regulations are applied shows us the players' hierarchical classification

21. There are also special areas with their own specific rules. The arena on MUD-1, for example, is an area where players can go to fight each other without having to fear the negative consequences of a player-to-player fight in the rest of the MUD. Player-killing is strictly forbidden in all other areas of MUD-1, and if someone would try to kill another player outside the arena, s/he would probably be banned from the MUD.

2. Player hierarchies

MUDs, like any other community, have a social structure. In both MUD-1 and MUD-2 this structure is very rigid and based on a strict hierarchy. This hierarchy is mostly dependant on a player's level on the MUD (as it is the case on MUD-1), although other elements, such as role-play ability (especially on MUD-2) or knowledge of the MUD, can also influence it. Upward mobility is possible by advancing in the game but once a player becomes an immortal, the levels remain fixed. One can only rise by getting a promotion from a superior immortal, and mostly it is only the implementor who has the power to do so. Player-levels are omnipresent on these MUDs, and can be consulted at any given time. When for instance a player on MUD-1 types "who", s/he gets a list that resembles the following.

- Players in MUD-1

- ----------

- [ Deity ] I hope to go to Heaven, whatever Hell that is -Mudder3 (idle, brak)

- [ Archangel ] Error 501: Mudder20 Not Implemented. (AFK22, brak)

- [Lord Champion] Mudder37 the killer attack champion

- [ Lord Knight ] Mudder41 the killer attack squirrel

- [ Hero Monk ] Mudder18 the Royal Cartographer

- [ Hero Cleric ] Mudder42, not quite Mudder37, but, it should suffice!

- [ Hero Psionic ] Mudder22 killer attack mouse

- [ 20 Druid ] Mudder4.5.2 (idle 3m)

- [ 15 Ranger ] Mudder12 the Hunter (AFK, idle 5m)

- [ 10 Druid ] Dimmu the Novice Herbilist

- [ 6 Warrior ] Mudder24 the Warrior

- 11 visible players.

- Total number of mortals in the game: 923.

The list is sorted according to level, starting with the highest (Mudder3) and ending with the lowest in rank (Mudder24). Besides the level, we also see the class of the character

24. The sentence behind the names is called a title. It allows players to give more information about themselves, their characters, or just to make some witty comment. Players can modify these once they reach level 20. Below that, the title is pre-set by the immortals and it changes automatically when a new level is gained. Behind the title we also get some information about idle-time and other flags, like the AFK-flag

25.

Players on MUD-1 and MUD-2, and the immortals as well, are classified into categories. There are newbies

26, player-killers

27, builders and coders

28. Every player also chooses a race

29 and a class when they first log on. And later they can join clans, guilds or tribes

30. This also tends to vary from MUD to MUD. While MUD-1 offers guilds but no clans or tribes, MUD-2 has a variety of clans and tribes, but no guilds. These organisations have their own specific hierarchy that can be just as rigid as the one of the MUD itself. Every organisation has their own leader(s) and they all have separate classifications for aspirant and regular members.

The hierarchy on MUD-2 is stricter than on MUD-1, mostly because its link with Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time-series is closely protected. There is a precarious balance between level of experience points and role-play level. During role-play one can only use the skills one knows code-wise

31 as a character, but it depends on the role-play level how well this skill can be used. This means that both levels are to be taken into account when we want to look at the hierarchy on MUD-2. In the following extract we witness a discussion between an immortal and a guild leader who wishes to get promoted. It shows the decision-making powers of the implementators.

- [OOC] Mudder2: "hrmm so when do i get promoted ?"

- [OOC] Mudder2 looks around and whistles innocently.

- [OOC] Mudder1: "Couple years."

- [OOC] Mudder2: "oh come on i like getting Mudder21 all buggy"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "I'm afraid if I promote you.. and mudder20.. mudder21 may commit suicide."

- [OOC] Mudder2: "good deal"

- [OOC] Mudder2 falls to the ground and rolls around laughing hysterically.

- [...]

- [OOC] Mudder2: "Mudder20 deserves to be promoted"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "I don't promote guildleaders that often. So don't hold your breath:)"

- [OOC] Mudder2: "i don't"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "I haven't even rp'ed mudder6's promo yet."

- [OOC] Mudder2: "hehe"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "I told mudder13 to do it."

- [OOC] Mudder1: "But mudder13 doesn't like mudder6."

- [OOC] Mudder2 falls to the ground and rolls around laughing hysterically.

- [OOC] Mudder1: "so he never will do it"

- [OOC] Mudder2 falls to the ground and rolls around laughing hysterically.

|

While other players are promoted by their guild leaders, the guild leaders themselves can only be promoted by the immortals. The first type of promotion only affects the role-play hierarchy and thus only has a modest impact on the overall hierarchy.

3. Formal rules of interaction

The formalised rules on the two MUDs are created by the immortals. Sometimes only the implementor, who owns the MUD, has the right to change these rules, and sometimes, like on our two MUDs, there is a council of immortals, strengthened with a few high-level characters, which can propose new rules or change the existing rules.

The formalised rules are enforced with punishments or at least with the threat of punishment. It is important to note that both immortals and players are bound by these rules, although the immortals do have some privileges on the two MUDs we studied. The form of punishment is usually mentioned in the same help-file as the rules, so we could say that these retaliations are also formalised. The main rules on MUD-2 can be invoked by typing "help rules" at the prompt. The player is informed of this when s/he first creates and every time s/he logs on after the initial creation. It is expected that every player takes the time to read them and thus also that they know and respect them.

-

- MUD-2 has three major divisions of rules, each having five major rules. The divisions are:

-

- OOC32 Rules

-

- 1) Be Respectful to All Mudders.

-

- 2) No Multiplaying

-

- 3) No Botting33

-

- 4) No Exploitation of Bugs34 or Immortal Powers

-

- 5) Ignorance is NOT an excuse.

-

- Player Killing Rules

-

- (You may Player Kill in the Following Situations)

-

- Player Killing is IC35 When Used:

-

- 1) To initiate a sneak attack in Major Roleplay Only.

-

- 2) Your IC actions are ignored during roleplay.

-

- Player Killing is OOC When:

-

- 3) If someone is harassing you in an OOC manor.

-

- 4) Both parties Agree.

-

- 5) Someone not in your guild is in your guild recall36

-

- Roleplaying Rules

-

- 1) Grouping is ALWAYS IN CHARACTER.

-

- 2) Never cut/paste information for roleplay of any kind.

-

- 3) Major Roleplay must always take place where your Major

-

- Roleplay Location is.

-

- 4) Major Roleplay Location is where your stories put you.

-

- To move you must post a story to ALL/Anyone Moving the

-

- subject: Movement: From to To, Who is Moving How?

-

- help distance chart for more info.

-

- 5) Your character may only use abilities that they

-

- gained OOCly, and only as well as their Roleplay Levels reflect.

- - Helpfiles are available for any terms you do not understand.

-

- ie: help Player Killing.

-

- Please contact the staff for any clarification. Mudder1 holds the final say in any matter.

The "Out Of Character" rules are the same as on most MUDs. The other rules are specific for MUD-2, hence the stress that is put on the issues about role-play on the MUD. The rules concerning player-killing have been changed on a number of occasions in an attempt to fit it in the concept of Role-Playing and "Out Of Character" killing

37, but we will get back on that in the section on collaboration and co-deciding in the discussion on generative powers in this paper.

Extensions to these basic rules can be found by browsing the help-files on the MUD. New rules will also be announced at the "changes" -section of the bulletin board. These rules are of course never definite. And again, the immortals (and in this case especially Mudder1) have the prerogative in the interpretation and implementation of these rules; witness the statement that

"Mudder1 holds the final say in any matter".

4. Etiquette / Netiquette / MUDiquette

Not the entire regulatory framework on the two MUDs is formalised, as part of it is embedded in norms of "good" behaviour. These are not included in any help-file, nor are they enforced by "official" punishments. They are supposedly internalised. The majority of the players and even the immortals abide by them and they all, through a diversity of social sanctions, enforce these non-formalised rules. As is the case in many forms of social sanctioning, processes of inclusion and exclusion are at the very core of this normative enforcement.

Etiquette (or widely accepted rules of public conduct) makes up a large part of the non-formalised rules. Another form is netiquette, which is an adaptation of etiquette with a focus on interaction on the Internet. But not all interactions are structured in a similar way on the Internet. Therefore we need to make a further distinction to include the etiquette that is specific for MUDs. Or even for each MUD separately since these rules vary according to the type of MUD. This last form we will call MUDiquette.

MUDiquette is a collection of MUD-specific non-formalised rules. It can be seen as a localised version of the more general netiquette, in prescribing how the interpersonal interaction should be conducted on a MUD. In our two MUDs this consists, among other things, of how to greet each other, what to do when a character gains a level, how to behave towards immortals, and what to say to a player whose character just died. Not abiding to these rules might attract negative reactions (or sanctions). Some of the rules of MUDiquette are also formulated negatively (as a restriction). On MUD-2, for example, the advertising of other MUDs is seen as something that is simply not done since it might make players leave. This rule is not found in the formalised help-files, and yet the players abide to this unspoken restriction.

- [Newbie] Mudder61: "do you know any muds that have the Asha'man38 and rand39 and stuff?"

- [...]

- [Guide] Mudder52: "not that I'm going to advertise here"

- [Guide] Mudder52: "i would get in trouble"

- [...]

- [Newbie] Mudder61: "why, i want to play on one, but i can't find any and it makes it almost pointless to make a male channeler40"

- [...]

- [Guide] Mudder52: "cause we don't advertise other muds here"

- [Guide] Mudder51: "you aren't supposed to advertise others muds on here while you play here. it isn't considered proper etiquette"

Although Mudder61 asks it nicely, the other players will not tell him of another MUD where he can create a male channeler. He will have to go look one up himself, or concede to the restrictions for male channelers

41 on MUD-2 and stay there. Although these rules are mostly non-formalised, they can also become formalised. Just like formalised rules will eventually be perceived as MUDiquette. The distinction between formalised and non-formalised rules in gaming practice may therefore not be as clear as portrayed here.

Player resistance to restrictive power aspects

The heavy load of these restrictions might create the expectation that the unequal power balance provokes fierce resistance. In contrast, a high degree of compliance can be observed on the two MUDs. Only a few rare occasions of resistance occurred. In the following excerpt we see a trace of resistance: one of the immortals (Mudder13) sets things straight after their decisions have been questioned. The immortal firmly reaffirms the decision made before, and re-establishes his own authority and that of the leader of the guard, with the following statement:

"I expect this to settle any disputes now, and give Mudder2 to handle any disagreements as he sees fit with consultation with Mudder1 and I" . The player (Mudder38) that questioned the decision gives in and apologises for having started the discussion. He does add the sarcastic note to his statement:

"Just trying to make sure Mudder21 gets the recognition he deserves. Didn't know it was against the rules". Although some resistance can be read in this exchange, it is marginal.

- Area: OOC - Note #494

- From: Mudder13

- To: towerguard whitetower

- Subj: Leadership within the Towerguard

- Time: Tue Nov 19 21:07:31 2002

- Lately I have heard from several sources, and seen on guildchat and through notes several disputes over who is the leader of the Towerguard, Mudder2 or Mudder21. Yes they both have the same rank but Mudder1 and I have both placed Mudder2 in overall command of the Towerguard. Mudder2 did the necessary Guild Leader RP's in order to obtain his rank and also handles all of the Guild Quests I assign to Towerguard every week. Imm alts cannot rise to a higher rank then GL 3 in any guild, nor should they ever be the head commanding officer of a guild since it is impossible to dedicate the necessary amount of time to both. I expect this to settle any disputes now, and give Mudder2 to handle any disagreements as he sees fit with consultation with Mudder1 and I.

- -Mudder13

- -

- Area: OOC - Note #496

- From: Mudder38

- To: whitetower mudder13

- Subj: Re: Leadership within the Towerguard

- Time: Tue Nov 19 21:25:55 2002

- -

- OK, sorry about the note then. Just trying to make sure Mudder21 gets the recognition he deserves. Didn't know it was against the rules.

|

Generative power aspects

Despite the relative long list of player restrictions, and the limited opportunities for resisting them, MUDs do provide the players with gaming pleasure through the interaction between the players and the MUD and through the interaction between the players themselves. From this perspective the social sphere of the MUD is highly dependant on the presence of sufficient players, which in turn is dependant on their pleasure. Through (the lack of) experiencing pleasure, players have the power to decide on the future existence of the MUD. Moreover the interaction on a MUD is not limited to the game itself, as ample fora for "out-of-character" discussion exist. This also creates possibilities for negotiation, and bypassing the rigid hierarchical structure. Thirdly, as has been mentioned before, some forms of collaboration and even more formal platforms of co-decision do exist. And finally, the MUD remains a community, which has several identities or sub-communities (such as newbies or guilds). On the basis of these identities specific allegiances can emanate from the gaming practices, thus strengthening the weak power base of the "ordinary" players.

1. (Lack of) pleasure

The main reason of existence of a MUD is the pleasure that this environment can produce for its players, who can take on a plurality of identities. The absence of pleasure would result in its demise. And while this is mostly taken for granted, it sometimes is explicitly mentioned. The following note was posted on MUD-2 and discusses a new idea that was brought up. The original idea was that when a player attacked a mobile, the mobile would get marked by that player, ensuring that only that player would be able to kill it and thus receive the experience points that he deserves. This came up during a discussion on kill-stealing, where one player killed a high-level mobile in a single blow because another player had wounded it severely. The first player received the experience points, while the other, who did all the work, did not get anything. The writer of this note, Mudder47, agrees that the implementation of this rule might "reduce the fun factor", unless the stipulation of one mobile was added as well. This shows that gaming pleasure is a rather important (and even explicitly discussed) issue on MUD-2.

- -

- Area: Ideas - Note #566

- From: Mudder47

- To: All

- Subj: RE: My mark...

- Time: Wed Nov 27 07:39:33 2002

- -

- Mudder36,

- I believe Mudder8 mentioned that the tag skill in question would only work on one mob at a time. If I tagged one Defender, then tagged another one, the previous tag would be erased and the second one would now be tagged. I agree that "marking" one's territory by tagging all the mobs would hinder levelling for all players and reduce the fun factor; however, the stipulation of one mob would alleviate the concern

|

Players do not only expect the opportunity to interact with the MUD itself, but also expect to interact with the other players. In the following example Mudder5 complains through a public channel about the fact that he does not get any response from the other players. Interestingly enough Mudder2, who is an immortal on MUD-1 and at that point in time at work, immediately reacts, thus showing that there is activity on the MUD. At the same time this message is combined with a clear indication of the presence of surveillance by (at least one of) the immortals.

- Mudder5 gossips "mmm"

- Mudder5 gossips "second attack next level"

- Mudder5 gossips "sounds usefull"

- Mudder5 gossips "you know"

- Mudder5 gossips "you shouldn't talk all at once, that's impolite"

- Mudder2 gossips "some of us work"

- Mudder2 gossips "some of us play"

- Mudder5 gossips "all work and no play makes mudder2 a dull boy?"

- Mudder2 gossips "in the evenings i have time to play"

- Mudder2 gossips "now i'm just keeping an eye on you"

|

One of the moments in time where the gaming pleasure becomes apparent is when a player moves up in the playing hierarchy of the MUD. In the example below a player has reached his third Lord-level

42, and he clearly shows his satisfaction. The varying reactions of the other players show the complexity of the game played at the MUD, as it is at least partially based on competition. The achieving of levels, and especially the Lord- and Lady-levels, is an essential part of MUD-1, which provides players the ability to distinguish themselves. Most MUDders though choose to congratulate MUDder38 with his achievement. A balance deemed acceptable by the players between both types of reactions is vital in the production of pleasure.

- [Info] Mudder38 "trained to lord level 3!"

- [Gratz] Mudder38: "GASP"

- [Gratz] Mudder38: "GASP"

- [Gratz] Mudder37: "MUDDER38!:P"

- [Gratz] Mudder6: "noooooooooooooooooooooooooooo"

- [Gratz] Someone: "noooooooooooooooooooo"

- [Gratz] Mudder6: "whore :p"

- [Gratz] Mudder8: "Mudder38!"

- [Gratz] Mudder38: "Hey... I rule :p"

- [Gratz] Mudder53: "gratz"

- [Gratz] Mudder6: ":p"

- [Gratz] Mudder81: "mudder38"

|

2. Negotiating solutions

People use the two MUDs not only to play the game in a rather solipsist meaning, they also want to communicate with the other players. The players have several channels through which they can communicate: there are public channels with specific purposes and there are private channels, which can be used for the communication between two players. These channels can also be used for (attempts in) negotiating solutions for both specific gaming problems and more structural characteristics of the gaming environment. Although the final decision on whether to provide answers or structural improvements rests again with the immortals, the players are provided with opportunities to negotiate and generate changes.

In the excerpt below, we can read the discussion between Mudder8's, who is exploring a new area, and Mudder29, who built that area. What this lengthy extract shows is that the warriors on MUD-2 feel discriminated because they do not have a skill to open locked doors without the proper key. The other classes, like channelers and rogues

43, do have that skill. During the discussion we notice that they all are trying to protect their own class, either by trying to get certain skills or by making sure that other classes will not receive the skills that they possess. It even reaches the point where they have no other arguments left and Mudder8's reasoning and bargaining is simply ignored or met with irony (see Mudder1's reaction). The attempt to negotiate a solution fails.

- [OOC] Mudder8: "Mudder29, there IS a key into this fort, right?"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "Yes"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "or is it another channies-and-rogues-only fort"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "godan isn't rogue/channie only"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "there is a key, but it's inside the fort"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "found a key INSIDE the fort, but it doesn't work"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "you first need a channie/rogue"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "the silver one?"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "yeah"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "well, is this like that one?"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "i'm not telling"

- [OOC] Mudder11: "It's

- [OOC] Mudder20: "snicker"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "cuz if it is, I'm wasting my time"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "has his lawyer write Mudder29 a long legal letter about anti-warrior discrimination"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "awww a warrior who wants rogue skills.. how cute;p"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "doesn't have to be the exact same skill"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "how about a strength-based "smash door" skill?"

- [OOC] Mudder1: "Why not just remove all the doors and keys on the mud?"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "*scream* all my secret stuff!"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "no...cuz you have to HAVE the skill"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "NOOOO! Warriors must not have it!"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "and you could make it a level 70 or 90 skill"

- [OOC] Mudder29: "all of the high level armour and super damage weapons I make"

- [OOC] Mudder8: "I mean, there are entire areas that we warriors have no access to w/o help"

|

3. Collaboration and co-deciding

Usually the immortals create the rooms and areas on the MUD. But since it is such a tedious work, inspiration does not always come easily. So, although it is the immortal that makes or remakes the space on (in this case) MUD-2, the mortal's input can be welcomed as well, as the note below illustrates. Mudder32 is trying to make the area "Carysford" enjoyable once again and kindly asks for ideas. He even goes so far as to give out rewards to the players with the best ideas by making it a quest (see the subject line of the posting) in order to ensure a minimum amount of response. Although the final decision (on which ideas to include) remains firmly in the hands of the immortal, these types of collaboration allow "ordinary" players to have a say on the structural and spatial characteristics of the MUD.

- -

- Area: Quests - Note #475

- From: Mudder32

- To: all

- Subj: A Small Quest (prizes negotiatable)

- Time: Fri Nov 15 23:48:59 2002

- -

- I am looking for ideas to enhance Carysford and make it memorable instead of that little village you levelled in. I dont have a ton of time so these ideas can only take a day to do. This includes aggressive mobs, ideas for mprogs, etc. The deadline is Tuesday, November 19th. I have a few inns, some restaurant type places, a stable, and a small neighbourhood. I look forward to your ideas.

- Mudder32

|

Another form of co-deciding that is in effect on both MUDs is the player council. The player council consists of high-level players and it is their job to convey the problems that players experience to the immortals. They can make suggestions to change certain formalised rules, but, as always, the final say is in the hands of the immortals. In the next note we can see how an immortal defends the balance between role-playing (RP) and player-killing (PK) at MUD-2. Not only does he refer to the importance of pleasure (" personal enjoyment" ), he also emphasizes the decision-making capacity of the player council.

- Area: OOC - Note #65

- From: Mudder125

- To: mudder1 immortal mudder6 mudder25 mudder15 mudder2 all

- Subj: Player Council Exam Number One

- Time: Sat Oct 19 12:08:21 2002

- -

- One of the most important decisions any MUD has to make is where the balance between RP and PK will lie. So far, this turn, I don" t have many complaints on this matter. A majority of the player base does an admirable job RPing regularly, and takes great personal enjoyment from this. It will be a grave error to reward players who RP with experience, money, etc. because then it loses its sense of fun and purpose.

- Acting as your character (RP) should be a great enough reward in itself. Once you resort to bribing people to RP, you are taking away genuine motivation to participate and influence the RP activities of this MUD. Recently, MUD-2 has been experiencing the difficulty of organizing large scale RP events, such as the battle for Malkier. This is very common and should have been expected.

- Most of the people involved have either full-time jobs or school. I happen to have both, so I can easily sympathize with them. There is nothing you can do to remove OOC priorities, so just keep trying Mudder13 *grin*. Now, the problem of PK. It" s an issue as divided and tedious to make a decision on as abortion. Someone is always going to disagree with what the immortal staff, and the player council, decides.

- One thing that I feel very strongly about on PK is that it CANNOT be allowed to have IC consequences. PK is just like RP, something you should do if you enjoy, within well-defined boundaries, and with moderated results.

- (...)

|

4. Community

MUD-1 and MUD-2 can be seen as communities that are based on a sense of belonging to a gaming environment characterised by a specific culture and language, a complex balance between personal achievement, competition and solidarity and protected by a highly rigid regulatory framework and hierarchy. Within this community different allegiances exist, based on specific identities and sub-communities. These identities and sub-communities can create forms of solidarity among players, which is often based on an antagonistic relationship with other identities and sub-communities. These forms of solidarity nevertheless improve the power base and generative capacities of the players involved.

On MUD-2, for example, we have Mudder1 and Mudder2 discussing the difficulty of levelling. When Mudder1 talks of his past experiences on MUD-3, which we did not study in this paper, he constantly uses the "we" -form. He also refers to "us big levellers" when talking about himself and his fellow-MUDders. Even although MUD-3 has ceased to exist for over a year now, Mudder1 still feels part of that community and even of the group of the "big levellers".

OOC Mudder1: "We had several levelling trains on MUD-3."

OOC Mudder1: "Sometimes though a few of us big levellers would group together."

OOC Mudder2: "personally i wouldn't let peeps have ic skills unless they get them levelling and finding trainers"

OOC Mudder1: "But normally we were more interested in pkilling."

|

5. Conclusion

The power relations in the two MUDs are clearly unbalanced. "Ordinary" players become docile virtual bodies that are confronted with a high degree of restrictions, with relatively little options for resistance and with little capacities for generating their own impact on the structure and functioning of the MUD. The restrictions caused by the rigid hierarchy, the formalised rules and their enforcement leave little irony in the deictic discourse the implementators and immortals use. Although some room for negotiation, solidarity, collaboration and co-deciding does exist, the overall effect produced by these workings of power approximates a quasi-authoritarian position. The only room for "real" resistance that remains (fortunately) left is the solution to simply leave the MUD, which may shed a different light on the often high player mobility and what Barney (2000) calls the lack of rootedness of virtual communities.

Two nuances should nevertheless be made: firstly MUDs are gaming environments and structuring rules are not an exception in this domain of the social. These rules have in some cases become part of tradition, being passed on for generations, while other (more commodified) games are considered incomplete without the booklet describing their rules. But it should not be forgotten that the game-as-game is surpassed on two levels. The simulation of play is surrounded by dialogues on the way the game is played. Players leave the world of simulation repeatedly for moments of reflexivity, which are as "real" as any type of communication. In other occasions that in-character and out-of-character mode even blend into each other. Moreover, the game-as-game is also surpassed because it constructs a community of players, with non-simulated consequences. Also at the ontological level the dichotomy between simulation and reality poses problems, especially when combined with the socially often-depreciated notion of leisure time. All the elements legitimise the importance of MUDs as sites where "genuine" and "real" discourses on power, authority, hierarchy, democracy and participation are produced.

As the analysis shows, these MUDs can hardly be considered as sites of democratic practices. When concerned with the democratisation of society at all levels, with the democratic learning which might take place in the diversity of local sites and with the role the Internet can play in these areas, the MUDs offer a troublesome negation of democracy.

Despite their problematic lack of internal democracy - and this is the second nuance - these MUDs do offer the players a fair amount of pleasure and the structural hierarchy and power relations contribute in the construction of a player's community. Rules have considerable integrative effects, they are guidelines that help new players fit in quickly and they offer the more experienced players a familiar and carefree environment. The strong management and the vertical power structure succeed in both MUDs in organising the creative process of (among many other things) the continuous construction of the MUD, in dealing with high player mobility and the resulting need to socialise new players quickly, and in stabilising the potential conflict that might arise during play. At the same time it should be noted that efficiency is not a sufficient reason to abandon more democratic solutions to the problems related to the organisation of creative processes, the socialisation of members and the resolution of conflict.

6. A brief note on ethics and participant observation

Analysts of MUDs (and on a broader level: virtual communities) are quickly confronted with the problem of observer anonymity. The problems of covert participant observation are well documented. It can be seen as a violation of the principle of informed consent, since the subjects of research are kept ignorant of the researchers true identity. The subjects have no other choice but to participate. Furthermore it can also become an invasion of privacy, since the observer can gain access under false pretence to certain personal details the subject would never knowingly give out to a researcher (Bulmer, 2001: 55). But, as Fielding (2001: 149-150) points out, sometimes it is not possible to work overtly, for example when studying settings where outsiders are regarded with distrust. But even in "normal" settings, it can be beneficial to observe covertly, since people tend to censor themselves or adapt their behaviour when they know they are being watched (De Waele, 1992: 48). In reality, however, the two methods of overt and covert participant observation often shade into each other, making every form of participant observation a combination of both overt and covert roles (Fielding, 2001: 150).

When using participant observation for the study of MUDs, we need to keep one peculiarity in mind: the fact that the people on the screen are mostly known only by their nicknames. Their "real life" names are not known to other players, and mostly not even to the immortals of the MUD. Consequently, this player-initiated form of anonymity makes it virtually impossible for others, like researchers, to identify the various people behind the characters on the MUD. Another difficulty that presents itself to researchers is that MUDs tend to generate quite some traffic. People come in and leave as they please. And, most importantly, the players do not have to provide a valid e-mail address upon character creation and if they do, it is only accessible by the staff of the MUD. It is clear that in such a setting it is impossible to get an informed consent from everyone present at any given time. Although there is some irony (given the subject of this paper) in this modus operandi, we have asked, and received, permission from the implementers of the MUD, as they are its highest authority. This, of course, does not imply that everything collected can be used disregarding the responsibility every researcher has towards his/her research-subjects. People's rights to privacy and confidentiality should be kept in mind when processing the collected data, ensuring their anonymity at all times, since although the persons behind the characters cannot be identified by their nicknames, their characters on the MUD can. Therefore, in our logs, all (nick)names have been changed, as well as the names of the MUDs. Each player received a pseudonym based on his/her order of appearance in the logs. This means that the first player in the logs will be called "Mudder1" and the second "Mudder2" . These numbers have thus nothing to do with rank or preference. Room descriptions were also omitted since they are irrelevant for the research and can lead to the identification of the MUDs.

References

Aycock, A. (1993). Virtual play: Baudrillard on-line. Electronic journal of virtual culture, 1, (7). -

- Aycock, A. (1995). Technologies of the self: Foucault on-line. Journal of computer mediated communication 1(2).

-

- Baker, P., Ward, A. (2000). Community formation and dynamics in the virtual metropolis. National civic review, 89 (3).

-

- Bakhtin, M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

-

- Barney, D. (2000). Prometheus wired: the hope for democracy in the age of network technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

-

- Bateson, G. (1976). A theory of play and fantasy. In: Bruner, J.S., Jolly, A., Sylva, K. (eds.), Play: Its Role in Development and Evolution. New York: Basic Books.

-

- Blackmon, W. (1994). Dungeons and Dragons: the use of a fantasy game in the psychotherapeutic treatment of a young adult. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48 (4).

-

- Bolter, J., Grusin, R. (2001). Remediation: understanding new media. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

-

- Bulmer, M. (2001). The ethics of social research. In: Gilbert, N. (ed.), Researching social life. London: Sage.

-

- Caillois, R. (2001). Man, Play and Games. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

-

- Casey, E. (1997). The fate of place. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

-

- Clark, D. B. (1973). The Concept of Community: A Reexamination. Sociological Review, 21.

-

- Cohen, A. P. (1989, 1985). The symbolic construction of community. London: Routledge.

-

- Coleman, J. S. (1961). The adolescent society. New York: Free press.

-

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

-

- Curtis, P. (1997). Mudding: social phenomena in text-based virtual realities. In: Kiesler, S. (ed.), Culture of the Internet. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

-

- Danet, B. (1998). Text as a mask: gender, play and performance on the Internet. In: Jones, S.G. (ed.), Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting computer-mediated communication and community. Thousand Oaks & London: Sage.

-

- Danet, B. (2001). Cyberpl@y: Communicating on-line. Oxford & New York: Berg.

-

- Escobar, A. (2000). Place, power, and networks in globalisation and postdevelopment. In: Wilkins, K. G. (ed.), Redeveloping communication for social change: Theory, practice and power. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

-

- Evard, R. (1993). Collaborative networked communication: MUDs as system tools. In: Proceedings of the 7th System Administration Conference (LISA `93). Monterey.

-

- Fernandez, J.W. (1986). Persuasions and performances: the play of tropes in culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-

- Fernandez, J.W. (ed.), (1991). Beyond metaphor: the theory of tropes in anthropology. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press.

-

- Fielding, N. (2001). Ethnography. In: Gilbert, N. (ed.), Researching social life. London: Sage.

-

- Fiske, J. (1993). Power plays, power works. London, Verso.

-

- Giddens, A. (1997). Sociology: third edition. Cambridge: Polity Press.

-

- Groos, K. (1898). The play of animals. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

-

- Groos, K. (1901). The play of man. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

-

- Gruneau, R. S. (1980). Freedom and constraint: the paradoxes of play, games and sport. Journal of sport history, 7 (3).

-

- Hampton, K., Wellman, B. (2001). Long distance community in the network society. American behavioural scientist, 45 (3). London: Sage.

-

- Haraway, D. (1991). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In: Haraway, D., Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

-

- Hart, S. (2003). Agora: Types of virtual worlds. January 14, 2003. Retrieved May 21, 2003.

-

- Hollander, E. (2000). On-line communities as community media: A theoretical and analytical framework for the study of digital community networks. Communications: the European journal of communication research, 25 (4).

-

- Hughes, L. (1983). Beyond the rules of the game: why are Rooie rules nice? In: Manning, F. (ed.), The world of play. West point, NY: Leisure press.

-

- Jones, S. G. (1995). Understanding Community in the Information Age. In: Jones, S. G. (ed.), CyberSociety; Computer-mediated Communication and Community. London: Sage.

-

- Kitchin, R. (1998). Cyberspace: the world in the wires. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

-

- Lancaster, K. (1994). Do role-playing games promote crime, Satanism and suicide among players as critics claim? In: Journal of popular culture, 28 (2).

-

- Lang, K., Lang, G. (1995). Studying events in their natural settings. In: Jensen, K., Jankowski, N. (eds.), A handbook of qualitative methodologies for mass communication research. London: Routledge.

-

- Lawrence, J. (s.d.). Kanga.nu MUD-dev list. Retrieved May 21, 2003 from https://www.kanga.nu/lists/listinfo/mud-dev/

-

- Lewis, J. (2002). Cultural studies: The basics. London: Routledge.

-

- Lewis, P. (1993). Alternative media in a contemporary social and theoretical context. In: Lewis, P. (ed.), Alternative media: linking global and local. Paris: Unesco.

-

- Lindlof, T. R. (1988). Media audiences as interpretative communities. In: Anderson, J. A. (ed.), Communication yearbook, 11. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

-

- Lyon, David (1994). The electronic eye: The rise of the surveillance society. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

-

- Martin-Barbero, J. (1993). Communication, culture and hegemony: From the media to mediations. London, Newbury Park, New Delhi: Sage.

-

- Marvin, C. (1988). When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

- Merton, R. K. (1957, 1968 enlarged edition). Social theory and social structure. New York: The Free Press.

-

- Mitchener, B. (2002). Agora. January 28, 2002. Retrieved May 21, 2003 from http://agora.cubik.org

-

- Morris, A., Morton, G. (1998). Locality, community and nation. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

-

- Murrey, J.H. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: the future of narrative in cyberspace. New York: Free Press.

-

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton.

-

- Preece, J. (2001). Sociability and usability in on-line communities: determining and measuring success. In: Behaviour & Information Technology, 20 (5).

-

- Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

-

- Rheingold, H. (2001). Mobile Virtual Communities. July 9, 2001. Retrieved May 21, 2003.

-

- Said, E. W. (1986). Foucault and the imagination of power. In: Hoy, D. C. (ed.), Foucault: a critical reader. Oxford: Basic Blackwell.

-

- Sefton-Green, J. (1998). Introduction: being young in the digital age. In: Sefton-Green, J. (ed.), Digital diversions: youth culture in the age of multimedia. London: UCL Press.

-

- Stephenson, W. (1967). The play theory of mass communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

-

- Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press.

-

- Toffler, A. (1970). Future shock. New York: Random House.

-

- Tonn, B., Ogle, E. (2002). A vision for communities in the 21st century. In: Futures, 34 (8).

-

- Tonnies, F. (1963). Community and society. London: Harper and Row.

-

- Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen. New York: Simon and Schuster.

-

- Van Dijk, J. (1998). The reality of virtual communities. Trends in communication, 1 (1).

-

- Van Dijk, J. (1999). The network society. London: Sage Publications.

-

- Van Dijk, J. (1999). The Network Society. London: Sage.

-

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

-

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1977). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. In Bruner, J. S., Jolly, A. Sylva, K. (eds), Play: Its Role in Development and Evolution. New York, Basic Books.

Footnotes:

1

Nico Carpentier, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB - Free University of Brussels), Nico.Carpentier@vub.ac.be

2Niky Patyn, independent researcher, niky.patyn@gmail.com

3LambdaMOO is the most widely used MOO-server. MOO is short for MUD, Object Oriented, which indicates that the MUD was written in an object oriented programming language. This allows for certain functionalities that were not available before, such as user-created objects and rooms.

4TinyMUD was designed for creating social and role-play settings, and thus did not include a combat system. MOO is also used mostly for social MUDs.

5Logs MUD2, 19-11-02.

6DikuMUD was one of the first widely available MUD-servers, developed at the university of Copenhagen, but based on AberMUD and the original MUD, written by Richard Bartle. LP-MUD is also derived from AberMUD and was written in the LPC-programming language.

7Although it should be noted that at the ontological level this distinction is less obvious than it seems.

8The fourth type of game Caillois distinguishes is Alea (chance).

9See for instance Bakhtin's (1984) discussion of the carnavalesque.

10Not all authors agree upon the distinction between the Foucauldian concept of productive power and the Giddean concept of generative power. We here follow the interpretation Torfing (1999: 165) proposes:

"Foucault aims to escape the choice between 'power over' and 'power to' by claiming that power is neither an empowerment, potentiality or capacity [generative power], nor a relation of domination [repressive power]".

11The length of the sessions and the interval between them changed according to several factors, such as the total of on-line players and whether it was at the beginning or at the end of our research. Therefore the gaps between sessions will be bigger near the end of the research period. After carefully reviewing the logs, we chose twelve logs for each MUD from the first month. These logs were the richest, or contained in other words the most useful information. Together, the twenty-four logs counted almost 200.000 words.

12External fights are with hostile characters called "mobiles" or "mobs", while in-fights are with other players. This second category is usually highly regulated, for instance restricted to a free zone for so-called player-killing. Both categories clearly introduce the notion of competition, linking it to the Agon-group of games that Callois has defined.

13According to the advanced MUD search-engine at Mudconnector.com

14Sometimes there are exceptions: on MUD-1 some players - so-called psionics or masters of the mind - have special powers that allow them to also skip these restrictions.

15With the "goto"-command, the immortals can choose to travel directly to a certain player, mobile or room.

16For example, there is a room with a secret door and a button. Nothing will happen until a player pushes the button. This means that the room was "listening" for someone who pushes the button. The action of pushing the button is what triggers the room.

17This is the prompt with the hit, mana en movement points.

18Logs MUD-1, 04-12-02.

19"Snoop" allows the immortal to see through the eyes of the player, thus seeing exactly the same as the target along with his/her own output.

20For example, when an immortal would type "at Mudder6 look", the immortal would see the same as when s/he would type "look" in the room where Mudder6 resides at that time.

21Experience points (or XP) are used to determine the level of a character: the higher the amount of experience points, the higher his or her level.

22AFK is the short form for "away from keyboard"

23Logs MUD-1, 05-12-02.

24The class is what one could call a profession. This ranges from warrior to thief and from priest to magician. Some MUDs (mostly role-play MUDs) also allow more common professions like carpenters, blacksmiths and merchants.

25Flags are indications that there is something special with a character or item. The idle-flag shows which player is idle, but most flags on items are invisible unless looked at after using the identify-flag. These item-flags show if an item has spells cast on it.

26Newbies are new players who are still learning how to play the game.

27Some MUDs allow "player-killing" (PK) where one player kills another. Some players enjoy this aspect of the game so much that they mostly play on the MUD to PK. These players are called "player-killers" or PK'ers.

28Coders can be seen as builders, but they change the MUD at a more profound level. While builders change it by modifying rooms, the coders change how the combat-system works or how magic spells have their effect.

29Race means the species a player wants to play. Some MUDs offer the more conventional fantasy races, such as humans, dwarves, elves, orcs, etc., while others even allow their players to play cats, dragons or butterflies.

30Clans, guilds and tribes are communities inside the MUD. The clan is mostly based on a similar interest or belief, while the guild is based on the profession of the players. Tribes are, rather logically, based upon the race of the players.

31Some skills are coded, which means that they can be gained automatically from certain mobiles on the MUD. Other skills can only be used during the role-play and are therefore called IC-skills or in-character skills.

32OOC is short for Out Of Character. In a role-play setting, where everyone plays a role, it can be beneficial to sometimes step out of that role in order to say something that is not related to the ongoing role-play. When players do this, they are OOC.

33"Botting" is the practice of using automated scripts in order to play on the MUD. A "bot" allows the player to leave his chair, while the scripts control his character.

34Bugs are, just like in other software, mistakes in the program-code. It is general policy that these bugs should be reported in order to get them fixed as soon as possible.

35IC is short for In Character. It is the opposite of OOC.

36Players have a "recall"-command, which allows them to instantly transport themselves to their guild.

37Players on MUD-2 can kill other players. When this fits in the role-play, we speak of IC-killing and it is allowed. However, when there is no IC-reason for the action, we speak of OOC-killing, which is forbidden on MUD-2.

38Asha'man are the male counterpart of Aes Sedai. It can be seen as a guild of male magic-users.

39Rand is one of the main characters in the Wheel of Time series.

40Logs MUD-2, 19-11-02.

41"Channeler" is the term Robert Jordan gives to magic users in his Wheel of Time-series.

42When a player on MUD-1 has gained the status of Hero, they can choose to become Lords or Ladies. There are ten Lord Levels.

43Rogues is the term that is used to group thieves, assassins, bandits, robbers, burglars and bounty-hunters.